Your child’s teacher just called—again. Words like “disruptive”, “defiant”, or “unfocused” were mentioned, and now you’re thinking: Why is my child acting out at school? They’re not like this at home. It’s frustrating, confusing, and (if we’re honest) a bit heartbreaking.

Children often misbehave at school because something feels too hard: the work, the rules, the noise, or the social pressure. “Bad behaviour” is usually a sign of stress, a missing skill (like self-control), or an unmet need (like sleep or food). Finding patterns and teaching replacement skills is the fastest way forward.

Key takeaways

- Look for patterns: when, where, and with whom the behaviour happens.

- Ask what your child is finding hard (work, friends, transitions, noise).

- Partner with the teacher on one simple plan and review it regularly.

- Support basics first: sleep, breakfast, movement, and calm routines.

- Get extra help early if behaviour is persistent, escalating, or unsafe.

Why school behaviour can look different from home

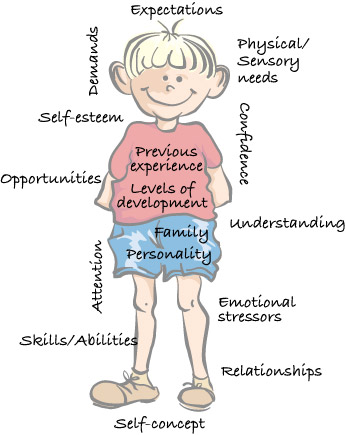

School asks children to do a lot at once: follow group rules, switch tasks quickly, sit still, cope with noise, and manage friendships—often with less one-to-one support. Some children “hold it together” in one setting and fall apart in another. Others struggle most where the demands are highest.

Common triggers for misbehaviour at school

Misbehaviour usually has a trigger. Once you spot it, you can target the right skill or support.

1. Pressure to perform academically

If your child struggles with a subject or fears failure, they may act out to escape work or avoid feeling “stupid”. Notice whether behaviour spikes during reading, writing, maths, tests, or timed tasks.

2. Difficulty adjusting to rules and routines

School is structured. Children who struggle with transitions, waiting, or sitting still may resist strict schedules. Ask when it happens most (for example, lining up, changing activities, or independent work time).

3. Social challenges with peers

Teasing, bullying, exclusion, or friendship drama can make school feel unsafe. Some children act tough; others withdraw. Try gentle, specific questions like “Who did you sit with at lunch?” and “What was the hardest part of today?”

4. Unmet physical needs

Hunger, poor sleep, sensory discomfort, illness, or even a growth spurt can lower patience and impulse control. A skipped breakfast or a late bedtime can look like defiance in class.

5. Lagging emotional regulation skills

Many children haven’t learned how to handle big feelings yet. If they can’t calm down, ask for help, or cope with disappointment, you may see shouting, refusing, or “shutting down”.

6. Mixed messages between home and school

Rules can differ across settings. If your child isn’t clear on expectations at school, they may push boundaries. Consistent language (for example, “hands to self” and “use a calm voice”) helps.

Impact of emotional well-being

Emotional well-being plays a big role in behaviour. Children often feel things they can’t explain, and school is where those feelings spill out.

Unprocessed feelings can lead to frustration

Sadness, anger, and fear can build up during the day. Without support, that pressure can come out as arguing, refusing, or disrupting lessons.

Anxiety can affect behaviour

Anxiety doesn’t always look like worry. It can show up as avoidance, perfectionism, irritability, or aggression—especially around new situations, tests, speaking in class, or separation.

Stress from home can spill into school

Family conflict, changes, grief, or financial stress can reduce concentration and patience. Even “good” changes (like a new baby) can affect behaviour for a while.

Difficulty expressing emotions

Some children don’t yet have words for their feelings. Teaching simple emotion labels (“angry”, “worried”, “embarrassed”) and body cues (“tight chest”, “hot face”) can reduce acting out.

Role of classroom dynamics

Sometimes the issue is less about your child and more about the fit between your child and the classroom.

Teacher–student relationships

A warm, predictable relationship helps children feel safe and cooperate. If your child feels misunderstood or constantly corrected, behaviour can worsen.

Peer influence and social pressure

Children copy the group. If classmates tease, provoke, or reward “funny” disruptions, behaviour can spread quickly.

Classroom structure and rules

Clear routines reduce misbehaviour. If expectations change from day to day, children may test limits to find the boundaries.

Teaching style and pace

Fast-paced or highly verbal teaching can overwhelm children who need more processing time or hands-on learning. Overwhelm often looks like “not listening”.

Overcrowded classrooms

When teachers have less time for individual support, children who need help may seek attention in unhelpful ways.

Parent–teacher communication

Strong communication helps you move from “What’s wrong?” to “What’s the plan?”

Why regular check-ins matter

Short, consistent check-ins can spot problems early and track progress. Ask for updates focused on patterns, not just incidents.

Ask the right questions

- What happened right before the behaviour?

- What does the behaviour look like, and how long does it last?

- What helps your child recover and re-join the class?

- Where are things going well (and what’s different there)?

Share context from home

Share changes that might affect school (sleep, separation worries, new routines). Also share what works: visual schedules, short breaks, choice-making, or a calm-down script.

Collaborate on solutions

A simple plan works best: one or two clear goals, one or two supports, and a quick way to track progress. Review it after 2–3 weeks and adjust.

Influence of external stressors

Stressors outside school can affect mood, focus, and self-control during the day.

Family challenges

Divorce, arguments, moving, or instability can overwhelm children. Acting out can be their way of asking for security.

Bullying and peer pressure

Children who feel unsafe may become withdrawn, defensive, or aggressive. If you suspect bullying, ask the school how they investigate and respond.

Academic stress

When work feels impossible, children may clown around, refuse, or avoid tasks. Extra support and reasonable adjustments can reduce the pressure.

Overstimulation

Busy schedules, little downtime, or lots of screens can leave children wired and irritable. A calmer routine can improve behaviour at school.

Effective strategies for support

With the right support, most children can improve their school behaviour. Start small, stay consistent, and focus on skills.

1. Understand the root cause

Track patterns for one week: the time, place, subject, and what happened right before the behaviour. Look for repeat triggers (for example, transitions, group work, or difficult subjects).

2. Teach replacement skills

Pick one skill to practise at a time, such as: asking for a break, using a “help” signal, taking three slow breaths, or using words instead of hands. Practise at home when your child is calm.

3. Make routines predictable

Children do better with structure. Prep bags and clothes the night before, keep bedtime steady, and build in decompression time after school (snack + quiet play).

4. Use positive reinforcement

Praise the behaviour you want to see. Be specific: “You stayed with the group during tidy-up” or “You asked for help instead of shouting”. Small wins add up.

5. Ask about extra support at school

If behaviour is linked to learning, attention, anxiety, or sensory needs, your child may benefit from targeted support (for example, movement breaks, seating changes, extra time, or a quiet space). If it’s affecting learning or safety, ask whether the school can do a simple functional behaviour assessment (FBA) and create a behaviour support plan (sometimes called a behaviour intervention plan).

6. Consider professional help if needed

If the behaviour is not improving, ask your GP, paediatrician, or a child psychologist for guidance. An assessment can check for anxiety, ADHD, autism, learning difficulties, or other factors that need a different plan.

When to worry and get extra help

Seek extra support sooner (rather than later) if any of these are true:

- Behaviour is unsafe (hurting self or others, serious threats, running away).

- School refusal is increasing, or your child is often sent home.

- There’s a sudden, major change in mood, sleep, or appetite.

- Problems are lasting weeks, not days, and support attempts aren’t helping.

- Your child seems persistently anxious, sad, or ashamed about school.

FAQs

Why is my child so badly behaved at school?

School behaviour issues usually come from stress, an unmet need (sleep, food, safety), or a lagging skill (attention, transitions, emotion control). Look for patterns, share information with the teacher, and teach one replacement skill at a time.

Why does my child behave well at home but badly at school?

Home and school have different demands. School is louder, faster, and more social, with less individual support. Some children also “mask” until they feel overwhelmed. Ask when the behaviour happens and what helps your child reset.

When should I worry about my child’s behaviour?

Worry more if behaviour becomes unsafe, escalates over weeks, leads to school refusal, or comes with big mood or sleep changes. If you’re unsure, speak with the school and your child’s health professional so you can rule out anxiety, learning issues, or ADHD.

Could learning difficulties or ADHD cause behaviour problems at school?

Yes. When work feels too hard, children may avoid, clown around, refuse, or melt down. Attention and impulse-control challenges can also make rules harder to follow. Ask the school how they check learning needs and what classroom supports are available.

What should I ask the teacher in the first meeting?

Ask for specific examples, what happened right before the incident, and what helped afterwards. Then agree on 1–2 goals and 1–2 supports, and set a date to review progress in two to three weeks.

How can I help my child regulate emotions before and after school?

Prioritise sleep and breakfast, and build calm routines. Practise quick tools like breathing, a “help” signal, or a short break. After school, offer a snack and quiet downtime before homework or activities.

Conclusion

Your child’s behaviour at school can improve, especially when you focus on skills, not blame. Start by finding the triggers, then work with the teacher on a simple plan. Stay patient and consistent—small changes add up, and your support really can shift your child’s whole school experience.